Astronomers have picked up something strange we’ve never seen before in space: bright bursts of low-frequency radio waves emitted three times per hour from a source in our Milky Way.

“This object appeared and disappeared in a few hours during our observations”, noted Natasha Hurley-Walker, radio astronomer at the International Center for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) and senior author of a paper on transmissions published in Nature Wednesday.

“It was completely unexpected. It was kind of scary for an astronomer because there’s nothing known in the sky that does that. And it’s really quite close to us – about 4,000 years away – light. It’s in our galactic backyard.”

The signals were discovered by Tyrone O’Doherty, a PhD student at Australia’s Curtin University, using the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA), a telescope located in the outback Down Under. Some 71 pulses were identified as coming from an object codenamed GLEAM-X J 162759.5-523504.3 in array readouts collected between January and March 2018.

Powerful, periodic bursts of radio waves are a feature of a number of known transient celestial objects. Fast radio bursts, pulsars and active galactic nuclei have been spotted before, although the signals Hurley-Walker and his colleagues studied were different. These pulses would arrive every 18.18 minutes over the course of a few hours at a time. The team said it is “an unusual periodicity that has, for [their] knowledge, previously unobserved.”

The mysterious signals seem to come from a type of object never encountered before. Fast radio bursts last only a few milliseconds, pulsars flash once every few seconds, and supernovae and active galactic nuclei tend to emit radio waves for even longer periods, on the order of days or month. The strange entity’s radio beams, however, last between 30 and 60 seconds.

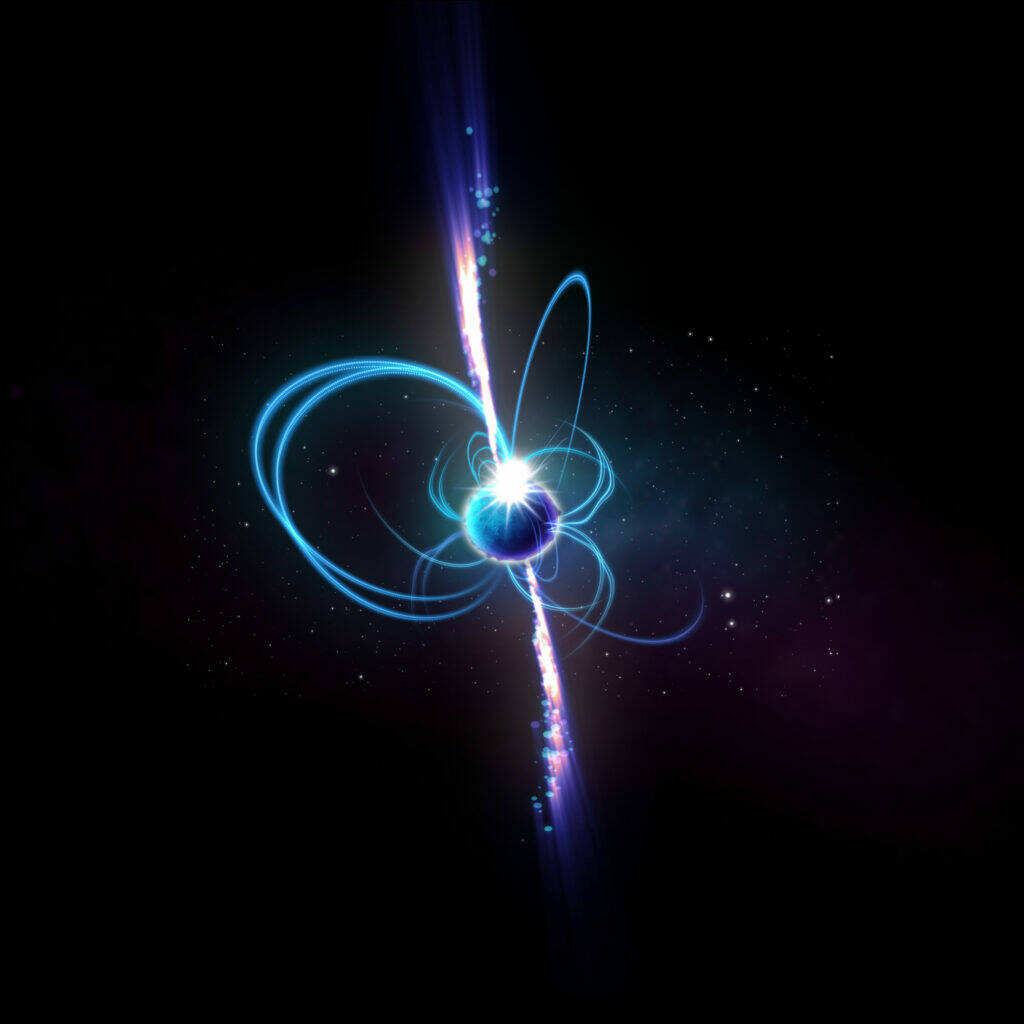

These flares are also highly polarized, indicating the presence of a strong magnetic field, said Gemma Anderson, co-author of the Nature paper and astronomer at ICRAR. She thinks the object is something very bright and smaller than the Sun.

The regular pulses every 18 minutes suggest it’s likely a single rotating object, Hurley-Walker said. The register.

“Orbital periods of 18 minutes are possible – but not for normal stars, they would crash into each other – only for two compact objects like exoplanets, white dwarfs, neutron stars or black holes “, she said. “No model produces such a bright radio emission from two objects orbiting each other, with such precision, and anything that produces any type of radio wave would also produce a ray emission X, which we don’t see. So if it’s not in orbit, it’s probably spinning.”

Long time, great mystery

It is possible that it is a very long period magnetar, a type of neutron star formed from the core of a dead white dwarf. Magnetars are typically only 20 kilometers (12 miles) in diameter and have strong magnetic fields. They generally emit X-rays in short bursts and are however associated with pulsars. If the mysterious object is a magnetar, it is unlike any other astronomer.

“Pulsars spin incredibly fast: a mass larger than the sun, a trillion times more magnetic, all trapped in a volume smaller than a city, spinning every second or even every millisecond. This generates an enormous amount of energy. [known as] ‘spin-down luminosity’ some of which is converted into radio waves or ‘radio luminosity’,” Hurley-Walker told us.

“As the pulsars lose energy, they spin slower and eventually ‘die’, becoming radio-silent. Our source spins slowly, so it shouldn’t be strong enough to generate radio waves – its radio luminosity is greater than its spin- luminosity drop.”

In other words, it looks much brighter than typical magnetars despite rotating so slowly. The other possible option is that it is a white dwarf star which is somehow able to generate a temporary magnetic field.

“The next step I’m taking is to build a real-time Milky Way monitoring program with the MWA, and I’m looking for funding to keep it running for a few years. That source was active in 2018, and it took two years to detect it, and another year to figure it out,” she said.

“If we had searched for these sources every day, we could have detected them in 24 hours and tracked them immediately with many other telescopes, and the MWA in a high temporal resolution mode. We could then have traced its activity over the three full months of activity down to the smallest detail.”

If the object is a white dwarf, she thinks it may be visible in optical wavelengths that could be detected using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. “This experience taught me that it’s worth trying to look at the sky in an entirely new way – you never know what you might find,” she added. ®