It’s not uncommon to see phone cameras with hundreds of megapixels these days. Ultra-high resolution cameras are even making their way to mid-range devices: Samsung’s upcoming Galaxy A73 packs a 108-megapixel camera. By default, however, this phone will definitely take 12-megapixel photos, just like the ultra-premium Galaxy S22 Ultra does. Why is that, though? What’s the point of all those megapixels if cameras continue to produce average-sized photos?

Digital camera sensors are covered in thousands and thousands of tiny, discrete light sensors, or pixels. Higher resolution means more pixels on the sensor – and the more pixels a sensor has in the same physical area, the smaller those pixels need to be. Since small pixels have less surface area, they aren’t able to gather as much light as large pixels, which means poor low-light performance. Megapixel phone cameras typically use a technique called pixel binning to get around this problem.

It’s technical, but in a nutshell, pixel binning, uh, bins groups of individual pixels into artificially larger pixels, which increases the amount of light data the sensor can collect when you press the shutter button. In the case of the Galaxy S22 Ultra (and presumably the future A73), groups of nine pixels are grouped together, which is how 108 megapixels translates to 12 (108 ÷ 9 = 12). Unlike Google’s Pixel 6 and 6 Pro, which have 50-megapixel primary camera sensors that always fire up 12.5-megapixel photos, the S22 Ultra gives you the ability to take full-resolution un-clustered photos straight from the stock camera app. We’ll take a look.

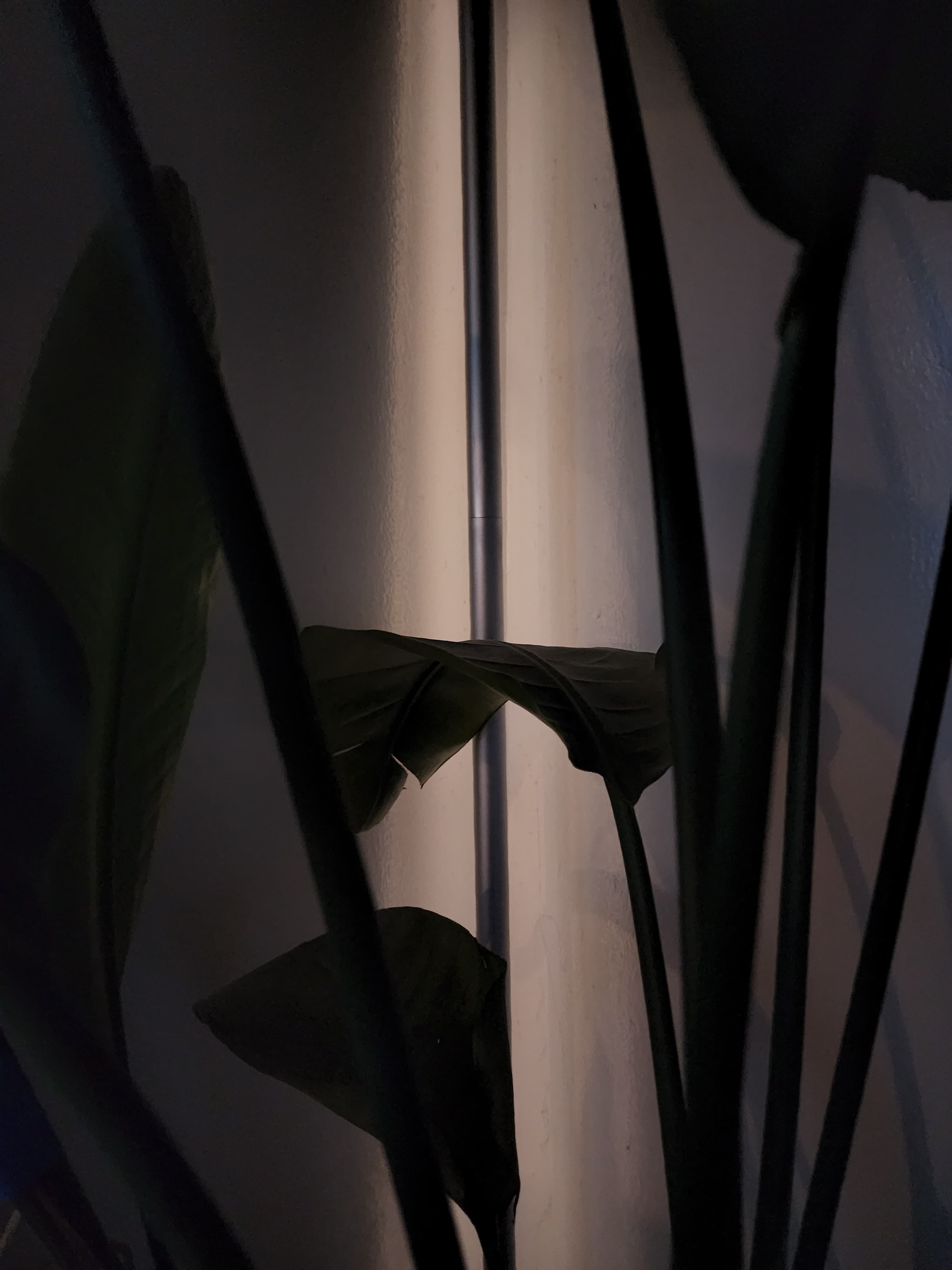

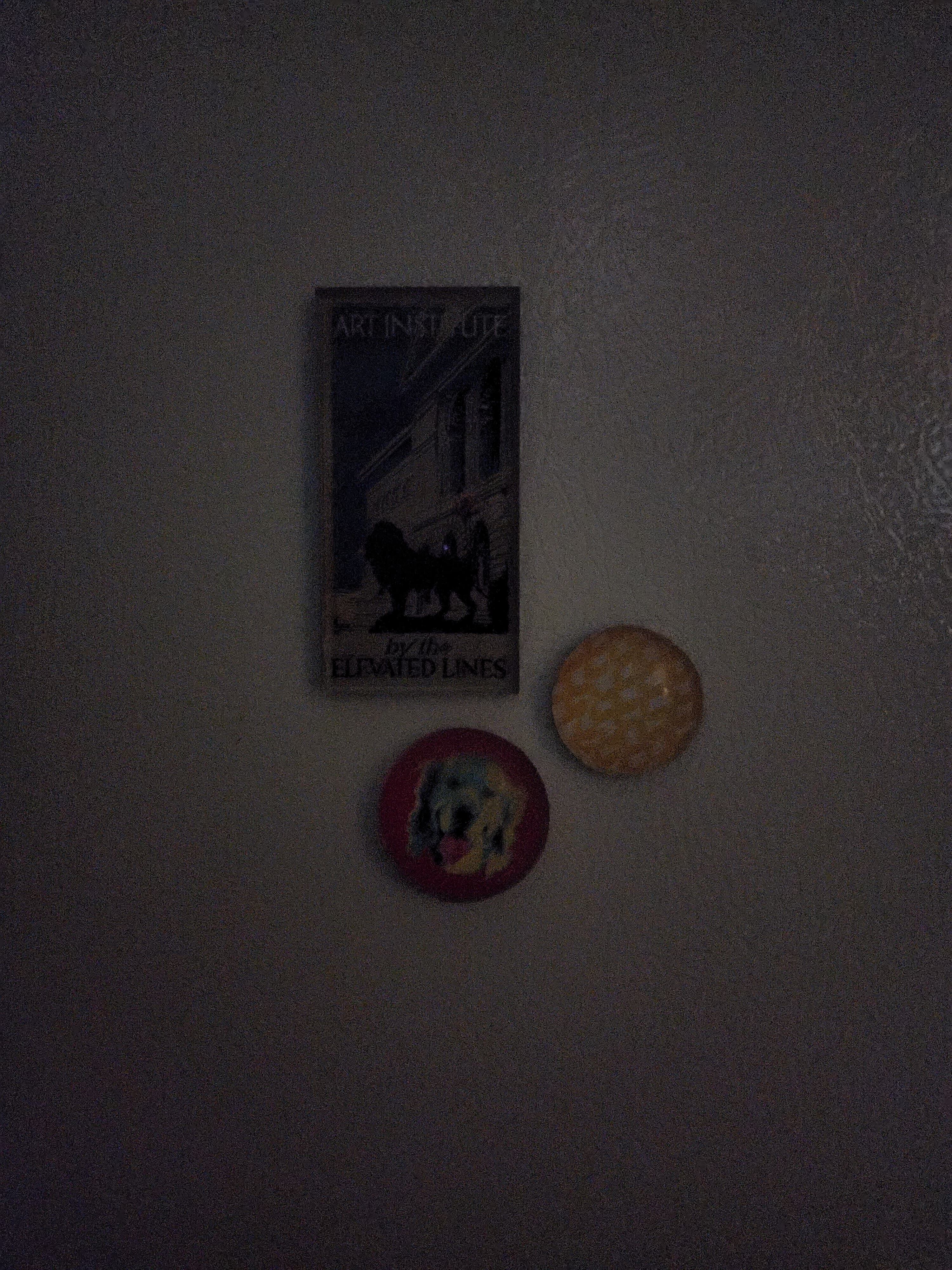

In each of these series of images, the first picture has been taken without pixel grouping and the second Photo has been taken with pixel grouping. (Ungrouped photo samples have also been resized from 108 to 12 megapixels.)

The photo above was taken outdoors just before sunrise – the lighting was a little dim, but already too bright for pixel clustering to have a significant impact on image quality. The photo came out virtually the same regardless of how I took it.

Here we are starting to see an improvement in image quality in the second photo, which was captured with pixel binning. There isn’t much of a difference in noise, but if you look closely the lines are more defined in the second photo – the edges of the first ungrouped photo look a bit jagged if you crop, especially in the shadows towards the lower right corner.

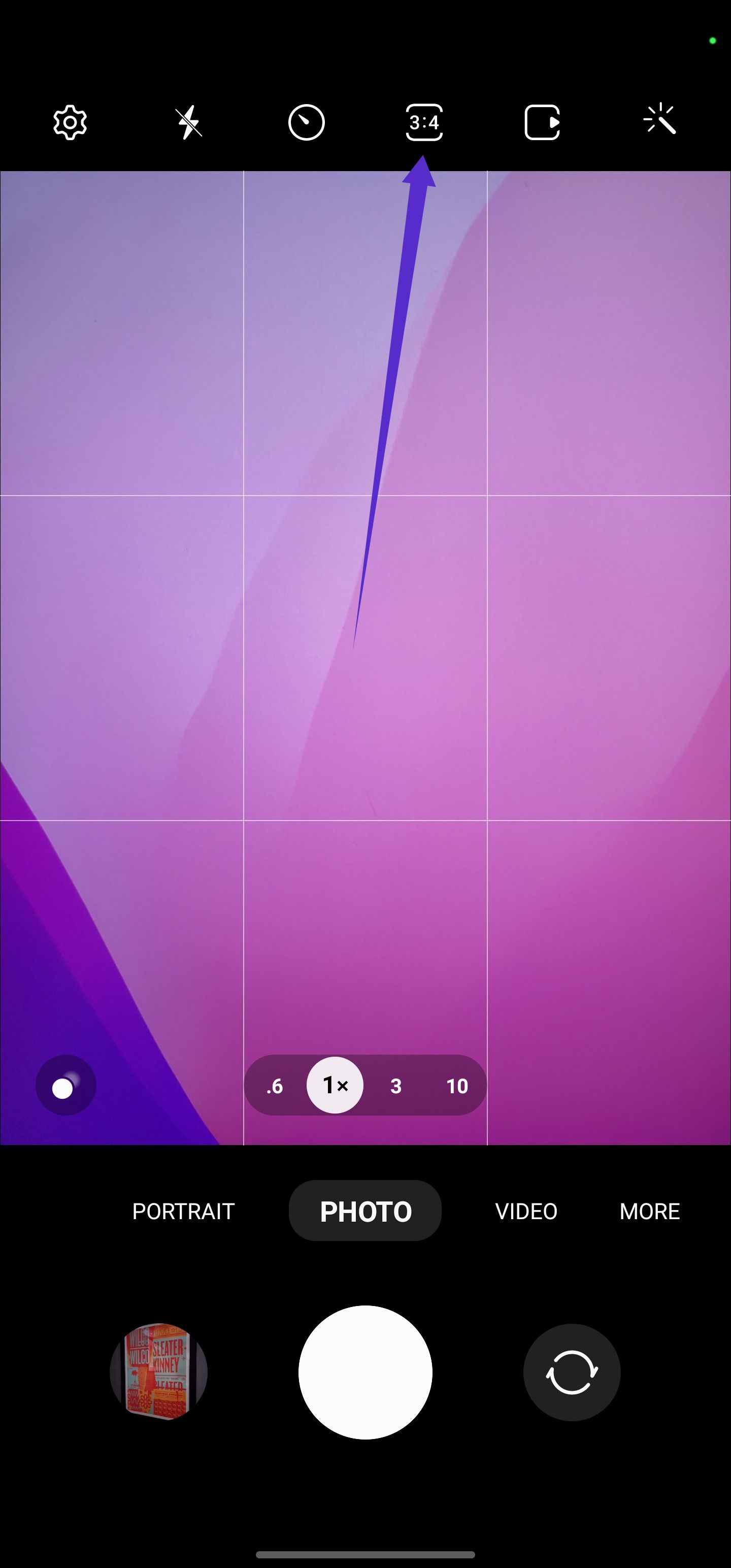

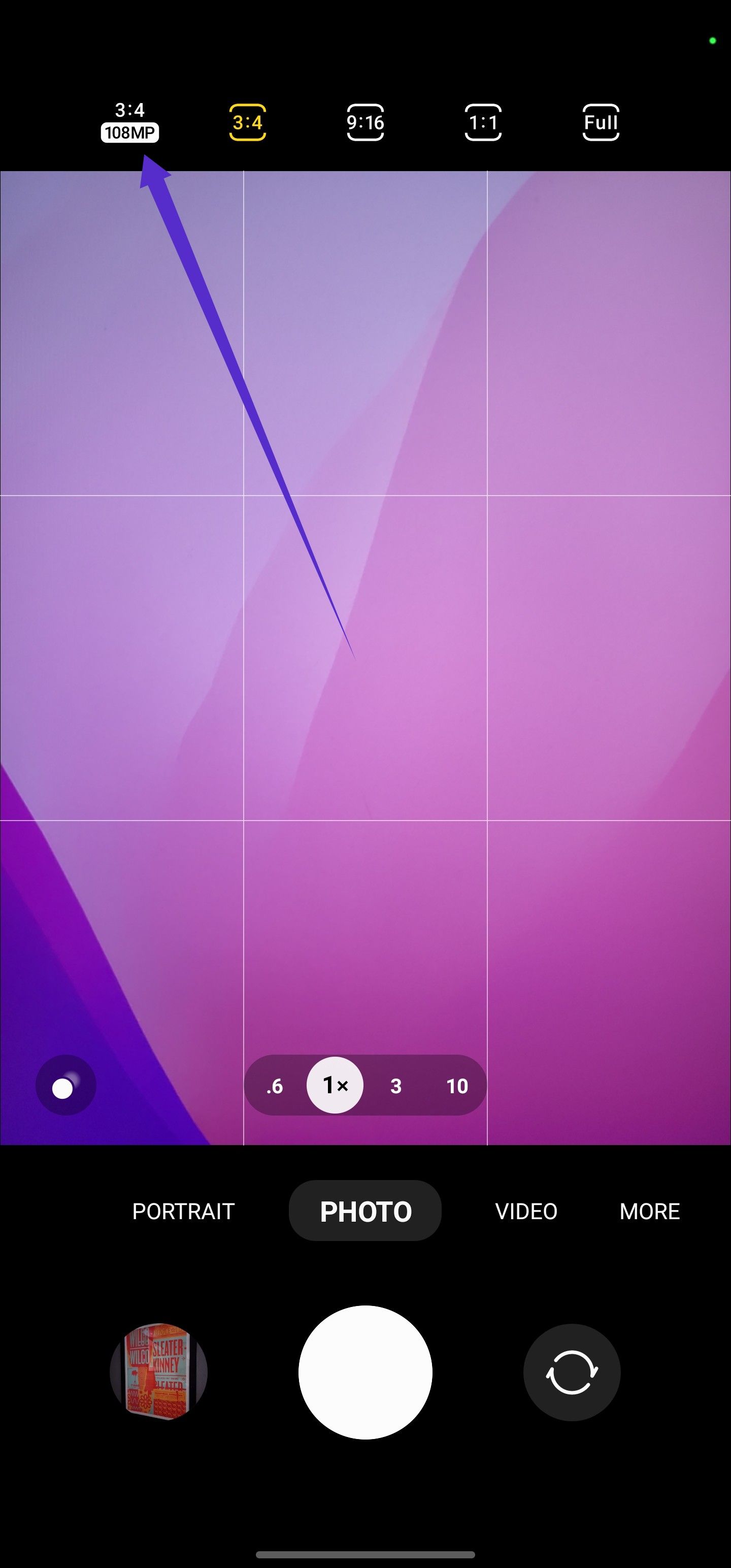

Want to take full resolution photos on your S22? The setting is actually hidden in the camera app’s aspect ratio switcher.

Note that access to the secondary cameras is restricted when you enable full-res shooting, although you can still zoom (with software) by pinching the viewfinder.

Unhappy with the performance differences in average light, I also took a few samples in really bad lighting conditions – conditions I wouldn’t expect most people to try to shoot in. In this set, the ungrouped shot (first) is clearly darker and noisier than the grouped shot (second), even without pixel-peep cropping. Neither goodbut it was very dark here.

Ungrouped/grouped/night mode

Same story here: the first photo is quite radically different from the second. The first photo, captured at full 108-megapixel resolution (which, again, has been scaled down to 12-megapixel here), is way louder than the one I took seconds later with the S22 Ultra’s default settings.

Taken in a very dark room against a dark colored wall, these photos show the most dramatic difference I’ve seen in my testing. The first image, captured without pixel binning and at 108 megapixels (reduced here to 12) is much noisier than the second, which was taken at the S22 Ultra’s default settings. Ironically, some detail is also lost at 108 megapixels: the text at the bottom right of the poster (which reads “NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE”) is completely unreadable in the first photo.

Pixel grouping is important for the physically tiny, high-resolution camera sensors that ship in many Android phones these days, as it helps them make sense of especially dark scenes. It’s a compromise: the resolution is considerably reduced, but the sensitivity to light increases. The huge megapixel count also gives you the ability to zoom with software when shooting 8K video – although that’s not a use case normal people will benefit from for many years to come. And of course, this is also part of marketing. A 108-megapixel camera looks a lot more impressive on a spec sheet than a 12-megapixel camera, even though they’re effectively the same most of the time.

From my experience here, it seems to take a really the dark setting for binning matters a lot, at least on the S22 Ultra in particular – in every instance where I saw a big difference, the scene was so dark I never thought to take a photo in first place (if not for needing low-light samples, anyway). On the other hand, shooting with the Ultra’s 108-megapixels doesn’t often squeeze much more usable detail out of the scene anyway, even in good light. Leaving the phone at its default 12-megapixel will provide the best experience most of the time, regardless of lighting.

Read more

About the Author