“Starquakes teach us a lot about stars, including their inner workings. Gaia opens up a gold mine for the ‘asteroseismology’ of massive stars,” said Conny Aerts, a professor at the Institute of Astronomy at KU Leuven in Belgium and member of Gaia. collaboration, a group of 400 researchers working on data from the project, in an ESA news item Release.

Previously, Gaia had detected radial oscillations — divergent movements from a common point — that caused some stars to periodically swell and shrink while retaining their spherical shape. The newly discovered oscillations were not radial.

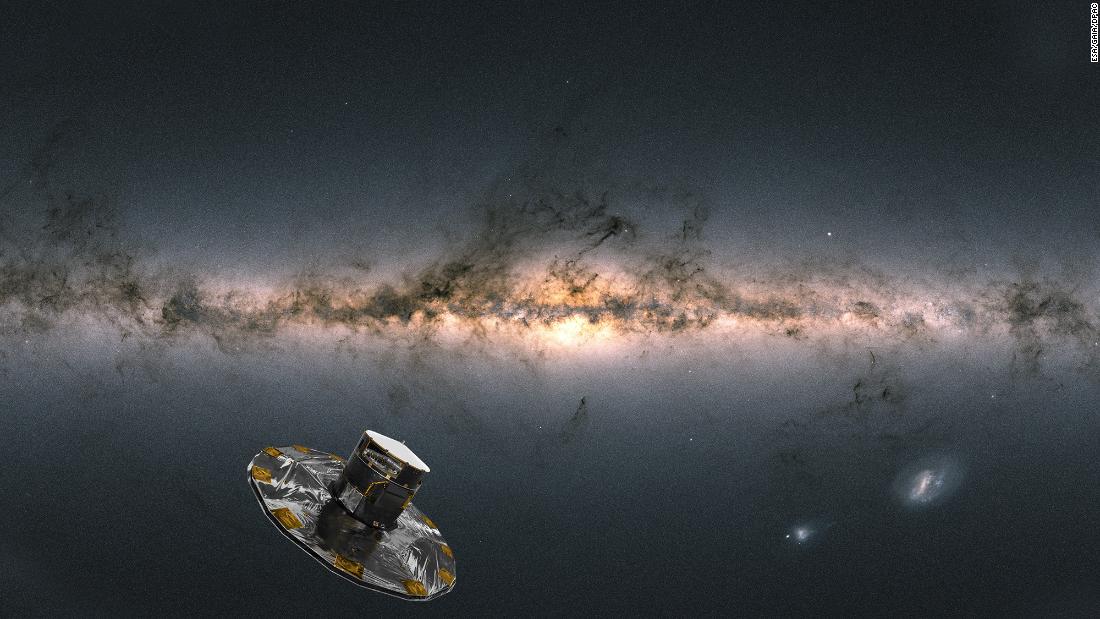

Gaia is uniquely positioned approximately 930,000 miles from Earth in the opposite direction from the sun. The spacecraft carries two telescopes that can scan our galaxy from a location called Lagrange Point 2, or L2. At this point, the spacecraft is able to stay in a stable place due to the balance of gravitational forces between the Earth and the sun.

It also means that the spacecraft has no interference from terrestrial light and can use the minimum amount of fuel to stay in a fixed position. The vantage point allows Gaia to have an unimpeded view and constantly scan our galaxy.

Much of the latest information about the Milky Way has been revealed by recently released spectroscopy data from Gaia, resulting from a technique in which starlight is split into its constituent colors, like a rainbow.

The data collected by Gaia includes new information about the chemical composition, temperatures, mass and age of stars, as well as how fast they are approaching or moving away from Earth. Detailed information on more than 150,000 asteroids in our solar system and space dust – what lies between stars – has also been released.

“Chemical mapping of Gaia is analogous to DNA sequencing of the human genome,” said George Seabroke, senior research associate for the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London, in a press release from the Royal Astronomical Society.

“The more we know about star chemistry, the better we can understand our galaxy as a whole. Gaia’s chemical catalog of six million stars is ten times larger than previous terrestrial catalogs, so it’s truly groundbreaking. The publications data from Gaia is telling. We know where the stars were and how they move. Now we also know what many of those stars are made of. said Seabroke.

“Unlike other missions that target specific objects, Gaia is a survey mission,” said Timo Prusti, Gaia project scientist at ESA.

“This means that by repeatedly surveying the entire sky with billions of stars, Gaia is bound to make discoveries that other, more dedicated missions would miss,” Prusti said. “That’s one of its strengths, and we can’t wait for the astronomical community to immerse themselves in our new data to learn even more about our galaxy and its surroundings than we could have ever imagined.”